Until the 1970s, symmetric encryption was the only type of encryption we know of.

Like the lock with multiple keys, when using symmetric encryption, the sender sends a message encrypted with a key, and the receiver must hold the identical key to decrypt a message.

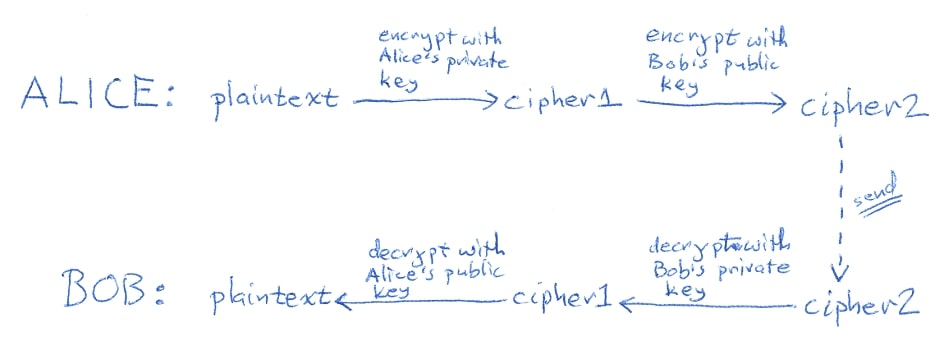

In cryptography, we usually introduce Alice and Bob as the sender and the receiver.

Alice and Bob must either meet physically or use some of the key exchange algorithms for both of them to have a copy of a secret key.

This brings another complication into the equation - numerous keys to be stored, as the sender possesses shared keys with each one of the receivers, and vice versa.

Non-secret encryption

During the 70s, mathematicians and cryptographers worked on the problem of sharing multiple secret keys with numerous parties.

That was the time when the idea of public key infrastructure was born.

In the essence of it, there was the thought that one key could consist of two distinct keys, one for locking and the other for unlocking the message.

This way, the sender should preserve just one key without maintaining a record of others.

One-way function

Let’s take mixing colours as a practical example of a one-way function. It is easy to create a mixture using two colours, but given the resulting colour, it’s challenging to find the original two colours that contributed to it.

If we convey a secret message in the form of colour, we could also use colours as encrypting keys. Every colour has its unique complementary colour so that they can be observed as a pair.

To establish a secret communication with Bob, Alice sends her inverted colour, e.g. her public colour. In the next step, Bob mixes her public colour with a message colour and sends it to Alice.

Alice then applies her private colour to that mixture, and having in mind that the complimentary colours cancel each other, she reveals the secret colour Bob sent her.

As finding the originating colours from the mixture is very hard to find, whoever is eavesdropping on this ‘colour’ conversation has little to no option to find out Bob’s secret colour easily. This makes for the rock bed of the public key infrastructure.

Quantum Computing

Even though it’s not the 70s anymore and we’re many times more secure cryptographically, there’s still a potential threat to current popular implementations of Public key cryptography.

Current implementations base their security on the difficulty of computing discrete logarithms which can be broken with sufficiently large quantum computers and systems that rely on it are also at risk.

SNARKs for example rely heavily on it, while STARKs don’t, the latter relies on hashing functions for its implementation. I’ll explore this topic in more detail, but for now, no need to worry as the Quantum tech isn’t there yet.